Köşedeki Sanatsal Varoluş

KAFKAS HABER AJANSI / BEDİR ALTUNOK

YAZAR NUR BANU ÇAĞATAY

Mekânsal olarak Avrupa’dayken, düşünsel olarak da burada olmanın tarihsel arka planından da kısaca bahsetmek giriş için anlamlı olur sanırım. İkinci Avrupa seyahatim ve her geldiğimde geldiğim yer olan burayı ve döndüğüm yer olan Türkiye’yi farklı gözlerle görüyorum. Her gitmelerim ve dönmelerim aslında Ben’i dönüştürürken, ‘orayı’da değiştiriyor. Hayatı ve uzantısal olarak mekânları anlamlandırmak bir felsefe yapmaksa, aslında bu gitmelerin ve gelmelerin felsefe yapma biçimini değiştirdiğini söylemek yanlış olmayacaktır. Yaklaşık üç yıldır varlık felsefesi ve varoluşçu felsefe ile ilgiliyim. Tezim ve aynı zamanda kitabım bu alanla ilgili. Hayatım ‘Varoluş’ ile ilgili diyebilirim. Bu yüzden buradaki yazılarım da çoğunlukla bu konu üzere olabilir. Sanırım bu istenç, beni sürekli Batı’ya iten şey. Batı felsefesinde iki farklı felsefe yapma şekli var. Bunlardan biri, Anglo-Sakson kültürde gelişen Analitik Felsefe diğeri Avrupa Felsefesi, yani Kıta Felsefesi’dir. Kıta felsefecilerinin temsilcileri arasında Husserl, Heidegger Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Beauvoir gibi düşünürler varken, diğer tarafta Russel, Wittgeintein, Carnap ve Quine’dan söz edebiliriz. Kıta felsefesinde, varolmanın ve düşünmenin en yüksek formu sanattır. Analitik felsefenin bilimselliği ve nesnelliği öne çıkartan tavrına karşın kıta felsefesinde filozofların hep; şiirlerle, resimlerle, sanatla iç içe olduğunu görürüz. Çünkü oradaki asıl mesele varoluş olduğu için varoluşun halleri içerisinde sanatsal bir halde varolmak, olma tarzının en yüksek derecesidir. Hayatımın anlarını duygularla iç içe yaşayan biri olarak, şiirler her zaman bana duygularla konuşabilme imkânı verdi, aynı zamanda duygularımı konuşturma imkânını da. Duygular diyorum çünkü benim için sanat ve sanatsal varolmak, aydınlanmanın sonucu olan ve beden ile ruhu ayıran Descartes felsefesiyle başlayarak keskin bir ayrıma giden yoldan ayrı bir yerde. Sanatsal yaşam benim için, duyguları dinlemek, gözlemlemek ve onları açığa çıkarmakla ilgili olmalı. Diğer türlü, yapay zekânın saniyeler içerisinde çiziverdiği bir resim veya yazdığı bir şiir duyguları dinlemekten ve yansıtmaktan yoksun olarak varsayılamazdı. Onun karalama yapmak gibi bir şansı yok. Oysa sanatsal olan kusurla birlikte varolur.

Burada şiirden bahsederken, sanatsal tavırlar arasında bir derecelendirme yapmak değil elbette ki amacım. Bu sadece benim yaşamla kurduğum dil diyebiliriz. Çoğu zaman görüp hissetmek yerine, okuyup hissetmeyi tercih edebiliyorum. Aslında arayışım; kendi hayatımın kavramları. Bu kavramlarla desen yapmaya çalışmakta sanırım henüz yeniyim. Şiir yazmaya yeni başladığım dönemde şöyle bir cümle kullanmıştım: “Şiir yazmak, ata binmek gibi.” Bir yanda yazmanın verdiği bir akışa kapılma coşkusu var bir yanda gizlediğini, kilitlediğini zannettiğin kapıları kıran ve ardındakileri sere serpe saçma hızı var. Şiir yazarken hakikati gizleme şansınız yok. Atın üzerinde korkunuzu gizleyemediğiniz gibi… Şiir de at gibi, gizlenen şeyin açığa çıkması için kontrolü ele alır. Sanırım bu yüzden kıta felsefecilerinin asıl derdi ‘varolmanın anlamı’. Anlam, şiiri yazarken, resmi çizerken Varlık’ın kendinden bile gizlediği şeyleri görüp anlamlandırmasıdır aslında. Mesele hep Ben’dir, Ben’in keşfidir. Kendini görebilen göz olmaktır… Berkeley’in dediği gibi: “Varolmak algılanmış olmaktır.” Eliot bir şiirinde şöyle demişti: “Tüm keşiflerimizin amacı dönmek olacak başladığımız yere, ve görmek olacak o yeri yep yeni gözlerle.”

Sizi ara sıra buraya, köşeme davet ediyorum, yeni gözlerle sizi uğurlamak üzere.

Gazetede bir yazara ait; şiir, bilimsel bilgi, felsefik bilgi içeren yazı neden köşededir? sorusu üzerine de düşündüm. Türkçede’ki bu köşe sıfatı İngilizce’de ‘column’ olarak kullanılıyor. Türkçe’ye sütun olarak çevriliyor. Köşe olarak da, sütun olarak da anılsa aslında anlam olarak derinliği aynı. Bu sorgulamanın ışığında şöyle bir sonuca vardım: Sütun/Köşe, bağlantısallığı sağlayan yerdir. Hem fizikte hem geometride böyledir. Farklılıkları birbirine bağlayan ve birbirleri arasındaki geçişkenliği sağlayan noktadır. Aynı zamanda kırılma noktasıdır da. Düz giden yol bir sapmaya uğrar, ihtimal noktasıdır. Aynı zamanda düşünme noktasıdır. Hayatın pek çok anında mekânların bir köşesine çekiliriz ve düşünürüz. Neden?’i Nasıl?’ı bulmak ve anlamlandırmak için. Hayatı ve kendimizi anlamak ve anlamlandırmak böyle mümkün. Varoluşsal sancıların cevapları çoğu zaman apaçık ortada değil köşelerde gizli…

Var olun.

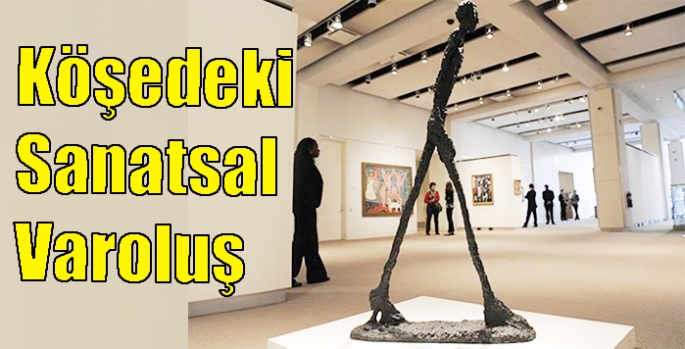

Ressam: Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti’nin yaptığı geometrik insan heykelleri, varoluşçu felsefenin etkilerini taşıyan önemli eserlerdir ve derin anlamlar içerirler. Giacometti’nin insan figürlerini uzatılmış ve geometrik olarak tasvir etmesi, insanın varoluşsal sıkıntıları, yalnızlığı ve çaresizliği ile ilgili temaları vurgular.

Giacometti’nin heykellerindeki insan figürleri, sık sık büyük ve uzun boyutlarda betimlenir. Bu uzunluğun ve geometrik şekillerin kullanımı, insanın soyutlaması ve yalnızlaştırılmasını ifade eder. Heykellerdeki insan figürleri, izole edilmiş ve çevresiyle etkileşimden yoksun olarak tasvir edilir, böylece varoluşsal yalnızlık ve insanın diğerleriyle olan ilişkilerindeki kopukluğu vurgulanır.

Ayrıca, Giacometti’nin heykelleri, insan figürünün belirsiz ve sıradışı hatları ile karakterizedir. Bu, insanın kimliğinin ve varoluşunun karmaşıklığını yansıtır. İnsanın iç dünyasındaki karmaşık duygular ve düşünceler, heykellerin soyut ve geometrik yapısıyla ifade edilir.

Giacometti’nin geometrik insan heykelleri, aynı zamanda insanın zaman ve mekân içinde kayboluşunu vurgular. İnsan figürlerinin ince ve uzun yapıları, sürekli hareket halinde olmalarını, bir anlamda sonsuz bir yolculuğun içinde olduklarını ifade eder. Bu durum, varoluşçu felsefede insanın geçiciliği ve sürekli değişim içinde oluşunu yansıtır.

Artistic Existence in The Corner

While being physically in Europe, it would be meaningful to briefly mention the historical background of being here from a conceptual perspective as well. This is my second trip to Europe, and every time I come back to this place, which has become my destination, and return to Turkey, my departure point, I see them with different eyes. Each departure and return transform not only “me” but also “there.” If life is a philosophical endeavor, a way to make sense of existence and its extensions in space, then it would’t be wrong to say that these departures and returns also change the way philosophy is practiced.

For about three years, I have been interested in existential philosophy and the philosophy of being. My thesis, and at the same time my book, is related to this field. I can say that my life is about “Existence.” That’s why these impulses continuously push me towards the West. In Western philosophy, there are two different approaches: Analytic Philosophy, developed in Anglo-Saxon culture, and The other is European Philosophy, that is, Continental Philosophy. Representatives of Continental Philosophy include thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Sartre, Beauvoir while in Analytic Philosophy, we can talk about Russell, Wittgenstein, Carnap, and Quine. In Continental Philosophy, the highest form of existence and thinking is considered to be art. Despite the emphasis on scientific rigor and objectivity in Analytic Philosophy, Continental Philosophers are often immersed in poetry, paintings, and art. This is because their main concern is existence, and existing in an artistic way within the states of existence is considered the highest form of being.

As being someone who lives moments of life intertwined with emotions, poetry has always provided me with the opportunity to speak through emotions and express my feelings. I mention emotions because, to me, living artistically stands apart from the enlightenment that Descartes’ philosophy brought, which sharply separated the body from the soul. For me, artistic life involves listening to emotions, observing them, and bringing them to the surface. Otherwise, a picture drawn or a poem written by artificial intelligence within seconds cannot be assumed to listen to and reflect emotions. It lacks the chance to sketch. However, the artistic essence coexists with imperfections. When I talk about emotions, I mean that for me, living artistically involves listening to emotions, observing them, and bringing them to the surface. Otherwise, the art generated by artificial intelligence, like a painting or poem created within seconds, would lack the ability to listen to and reflect emotions. It wouldn’t have the chance to sketch. On the other hand, artistic expression coexists with imperfections. When I talk about poetry, I’m not trying to rank different artistic attitudes; it’s just the language I use to understand my life. Many times, I prefer to read and feel rather than see and feel directly. In fact, my quest is to find the concepts of my own life and attempt to create patterns with them, which is something relatively new to me. When I first started writing poetry, I used the phrase: “Writing poetry is like riding a horse.” On one hand, there is the enthusiasm of surrendering to the flow of writing, and on the other hand, there is the force that breaks the hidden and locked doors and reveals what’s behind them in a chaotic speed. When writing

poetry, you have no chance to hide the truth. It’s like riding a horse; you can't hide your fear. Poetry, like a horse, takes control to reveal what is concealed. I believe this is why Continental Philosophers are primarily concerned with the “meaning of existence.” In poetry or when drawing a painting, meaning is about understanding and making sense of the things hidden even from Existence itself. The main issue is always “the self” and the discovery of I. It is about becoming the eye that can see itself, as Berkeley said: “To be is to be perceived.” As Eliot once said in a poem: “All our explorations will be to arrive where we started, and will be to see there with entirely new eyes.”

I occasionally invite you to this corner, welcoming you with new eyes.

Regarding the question of why a piece that includes poetry, scientific knowledge, and philosophical knowledge belongs to a column in a newspaper? I also pondered upon it. "In English, the adjective ‘köşe’ is translated as ‘column.’ In Turkish, it is also translated as ‘sütun.’ However, whether referred to as ‘köşe’ or ‘sütun,’ the depth of meaning remains the same. In light of this inquiry, I have come to the following conclusion: A column/corner is a place that establishes connectivity. It’s the same in physics and geometry. It’s the point that connects differences and provides their transitions. It’s also the point of fracture. A straight path may deviate, becoming a point of possibility. It’s also a point of reflection. In many moments of life, we withdraw to a corner and think. Why? To find and make sense of the “whys” and “hows.” This is how we can make sense of life and ourselves. The answers to existential agonies are often not explicitly apparent but hidden in the corners.

To being.

Artist: Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti’s geometric human sculptures are significant works influenced by existentialist philosophy and carry profound meanings. Giacometti’s portrayal of human figures as elongated and geometric emphasizes themes of existential anguish, loneliness, and helplessness.

In his sculptures, human figures are often depicted in large and elongated dimensions. The use of elongation and geometric shapes signifies human isolation and alienation. The figures in the sculptures are portrayed as isolated and devoid of interaction with their surroundings, highlighting existential loneliness and disconnection from others.

Furthermore, Giacometti’s sculptures characterize human figures with uncertain and unconventional contours, reflecting the complexity of human identity and existence. The abstract and geometric structure of the sculptures conveys the intricate emotions and thoughts within the human psyche.

Giacometti’s geometric human sculptures also emphasize the notion of human disappearance within time and space. The slim and elongated structures of the human figures suggest perpetual movement, implying they are part of an infinite journey. This aspect reflects the existentialist idea of human transience and continuous change.

In conclusion, Alberto Giacometti’s geometric human sculptures are profound works that carry the influence of existentialist philosophy. They poignantly express themes of existential anguish, loneliness, and the complexity of human existence. The sculptures portray the ephemeral nature of human life and the perpetual search for meaning within the context of time and space.

(BA-BA-S) GAZİ KARS (KHA) / KAFKAS HABER AJANSI / BEDİR ALTUNOK